Veering away from our normal coverage of coolers, today we're taking a fresh look at the subject of benchmarking. Since I started reviewing coolers for Tom's Hardware, I've often thought of how to make my reviews better and show results that users can relate to their real-world usage.

Beginning with my initial review of Arctic's Liquid Freezer III, I've been placing a stronger emphasis on testing methodology and what I feel are poor testing methods, because I feel that the bar for cooler reviews on the market is rather low.

Over the past year, and especially in the last few weeks, I've spent a lot of time exploring different methods of testing, with the aim of improving my own testing methodology. While I might sometimes criticize what I consider to be failings of others' testing, I apply that same level of criticism to my own published works and have realized that my cooler reviews have a very significant flaw.

As a result, I'm updating the w ay I test coolers. I was originally going to wait until later this year when next-generation AMD and Intel CPUs were available, but I've recently moved across the country to a new location due to an unexpected opportunity, providing an opportunity to change things up a little bit ahead of schedule. Before we dive into our new methods of cooler testing, let's take a quick look at what I consider to be failures in testing methodology that are present in many cooler reviews.

Bad benchmarking practices❌ Poor Ambient Temperature Control

One of the biggest factors that can influence the results of a cooler is the ambient temperature.

While most of the higher-profile cooling reviewers control this factor well, I've seen some sites that list a variance in ambient temperature of up to 4 degrees C (7.2F), which leads to a huge margin of error for test results.

A big red flag in some cooler reviews is a lack of any information regarding ambient temperature.

I strictly regulate the ambient temperature while testing CPU coolers to 23C.

❌ Open Bench Testing

Some reviewers test CPU coolers on an open test bench, the idea being to remove any variables other than the cooler. The problem with this type of testing is that it doesn't actually represent the sort of environment a cooler will deal with in the real world.

Due to the enclosed nature of a case, the ambient temperature within your system will be higher than that outside – increasing the difficulty of cooling a CPU. Testing outside of a case makes it a lot easier for the cooler to do its job, in turn making weak coolers look stronger than they really are.

❌ Thermal Plate Testing

Some test CPU coolers by using a thermal plate, instead of using a CPU. This generally suffers from the drawbacks of open bench testing but also doesn't effectively emulate the heat from a CPU. A thermal plate generally evenly distributes heat, with a low overall thermal density. CPUs, on the other hand, generate most of their heat in concentrated hotspots. This is much more difficult to cool.

You can think of a thermal plate like typical a cigarette lighter: you can take that flame and put it against your hand for a quick moment and, while it will be uncomfortable, you won't be hurt seriously. On the other hand, a CPU is like a concentrated butane torch lighter that produces a blue flame – if that touches your skin at all, you're in for a painful time.

❌ Using old CPUs to test coolers

Using an older generation CPU is certainly better than using a thermal plate, but it might not accurately represent the performance of a cooler on a more modern platform. The reason is the same: thermal density. Due to a combination of lower clock speeds and larger manufacturing processes, older CPUs aren't quite as diffic ult to cool as modern Intel "Raptor Lake" and AMD Ryzen 7000 and 9000 series CPUs.

❌ But wait, there's more!

There's one other significant failing in common cooler testing, and it's one that my own reviews have failed to account for. Before we dive into that, let's take a quick look at the testing system that I've used for this article (and will be using going forward), what isn't changing in our cooler reviews, and how I view Arctic's Liquid Freezer III.

What isn't changing in our reviews✔ Noise normalized testing

One of the most popular tests in my reviews has been noise normalized benchmarks. This is when all coolers have their noise output set to the same level. This is primarily a way of testing how efficient the cooler is, but it is also how I personally prefer to run CPU coolers. The computers I use outside of testing have their fans set to a static speed with low noise levels.

✔ Strength CPU testing

The biggest re ason I ended up disappointed with Arctic's Liquid Freezer III was that in maximum strength CPU testing, its performance was comparable to good air coolers, and it failed the standards I typically hold AIO liquid coolers up to.

On the testing setup I'm using today, I first tested the Tryx Panorama 360 ARGB AIO with Intel's i7-14700K in the new testbed, and the AIO was able to keep the CPU under TJ Max (the max temperature the CPU is designed to handle before throttling) allowing unrestricted performance. This is similar to my results with the strongest liquid coolers with Intel's i7-13700K, such as Lian Li's newly launched HydroShift AIOs.

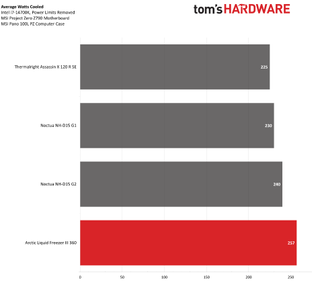

When I tested the Arctic Liquid Freezer III with Intel's i7-14700K, the results were similar to my initial review: it "failed" this test because the CPU reached its maximum temperature and had a small amount of thermal throttling. As such, I measured its maximum thermal performance by measuring the watts cooled by th e cooler.

For today's article explaining our new testing methodology, I've only tested the Liquid Freezer a gainst a limited number of coolers, because the purpose of this review is mainly to explain our new testing methods.

In maximum strength CPU-only testing, the Liquid Freezer outperforms Noctua's latest NH-D15 G2 air cooler. Based on the results with my previous i7-13700K-based testing platform, I would imagine that Thermalright's Frost Commander 140 or ID-Cooling's A720 air coolers likely provide similar performance as the LF3 in this scenario - though I can't say for sure until I've retested them.

✔ Low-strength CPU testing

Our easiest test is a 125W workload, and in this scenario temperatures don't really matter per se. This test is more to demonstrate the maximum noise levels that users might encounter in less-stressomg workloads, and will re,aomg part of our future reviews.

What's changing in our reviews▶ Different Location, Higher Humidity

I used to live in a desert, where the relative humidity was very low - typically under 25%. My n ew home is in a humid area, and the relative humidity is typically between 60 and 70% indoors. This will increase the difficulty of cooling to some extent, as cooling can be easier in a dry climate.

▶ MSI's Project Zero Z790 & Pano 100L PZ Black Mid-Tower Computer Case

I've recently been testing coolers using MSI's Project Zero Z790 motherboard and Pano 100L PZ case. You can check out our full build story at the link above, but the long story short is that Project Zero makes it easy for even the most inexperienced user to become a master of cable management and create builds that stand out from the crowd.

Most of my recent CPU Cooler reviews have featured Intel's i7-13700K or AMD's Ryzen 7 7700X. With today's testing, I've increased the cooling difficulty ever so slightly, using Intel's i7-14700K for the CPU in our testing system.

▶ Iceberg Thermal's IceGale Silent PWM system fans

I tested a few different pairs of fans before settling on Iceberg Thermal's IceGALE Silent fans. True to their name they have low noise levels and good thermal pe rformance. These fans are also fairly cheap – it's only $21.95 for a 3-pack of the PWM versions. The standard, fixed-speed version is even cheaper at only $16.95.

Components will change at some point, but the overall testing methodology I'll demonstrate below should remain consistent with upcoming reviews.

After contemplating different ways to improve cooler reviews, I came to the conclusion that my reviews also failed that standard, because they lacked one important consideration. Previously, I used a 175W CPU-only workload to emulate medium-intensity workloads and considered my 125W workload to be representative of gaming.

But that 125W test hasn't truly been representative of gaming, because it is missing one vital component: a graphics card. This is important because the impact of heat from a dedicated graphics card affects how well an air cooler can dissipate heat.

Prior to testing, I theorized that a workload that more accurately represents a gaming scenario would cause the Liquid Freezer III to better stand out compared to air coolers. To test that theory , I ran two tests with combined CPU + GPU loads. For these tests, we're using ASRock's Steel Legend variant of the Radeon 7900 GRE with a full GPU load, which consumes approximately 275W while running benchmarks.

Not all games will consume the same amount of power. Some are more CPU intensive and will cause higher CPU temperatures; others won't stress the CPU as hard. I briefly tested a variety of games with Intel's i7-14700K and in those titles, the highest CPU power consumption I observed was around 170-175W. To emulate CPU-intensive titles, I choose a slightly lower power limit: 165W.

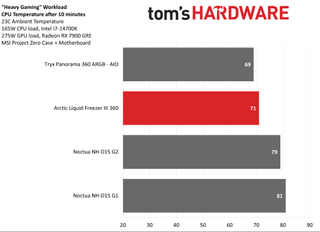

For this more difficult scenario, I primarily tested Arctic's Liquid Freezer III against both versions of Noctua's NH-D15 – but I also included one stronger AIO. The LF3 was behind the competing AIO by 2C, but it outperformed Noctua's flagship coolers by 8-10C.

Because most users will have their fans tied to a curve, the lower temperatures of the CPU can result in much lower fan noise levels compared to air coolers in CPU-intensive games.

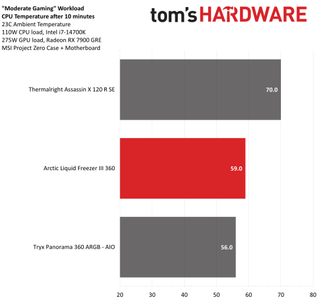

The second test of this type i s with a lower CPU power limit of 110W, which is similar to the power consumption you'll see with Intel's i7-14700K in games that are moderately CPU intensive. In this test, an entry-level Thermalright CPU cooler had the CPU at 70 degrees Celsius. Arctic's Liquid Freezer III was significantly cooler at 59C – an 11C difference!

This is a fairly significant gap in thermal performance. Most motherboards will engage moderate fan speeds above 70C, whereas they'll barely push the fans under 60C. That results in much quieter noise levels during your gaming experience.

Conclusion

Our previous review of Arctic's Liquid Freezer III was tested with CPU-only workloads, but these don't tell the whole story of how a cooler will perform.

In workloads like gaming where there is significant heat output from a dedicated graphics card, the Liquid Freezer will keep your CPU running cooler – and your noise levels lower – in comparison to high-end air coolers like Noctua's NH-D15.

With this in mind, my views on Arctic's flagship AIO have become more nuanced. The Liquid Freezer III 360 is a good value for gaming or users whose workloads are primarily GPU intensive.

However, bec ause it fails my maximum strength CPU-only tests, I would not recommend it for users whose workloads can utilize the full power of a modern multi-core CPU. For those users looking for a similarly priced alternative to the Liquid Freezer III that won't choke under the heat of the most intensive CPU workloads, I would recommend Iceberg Thermal's IceFLOE Oasis instead.

What do you think of our new testing methodology? If you have any thoughts or suggestions, please leave a comment. I value and listen to the feedback given on my reviews and hope you find these articles useful for your building and upgrade decisions.

0 Comments

Post a Comment